There has been much jest made of the Department for Transport advertising the role Head of Uncertainty. But the narrative around uncertainty can have a profound impact on the direction of transport policy.

It was perhaps a predictable PR risk to advertise for somebody to head up delivery of “uncertainty” for transport at a time when the nation is full of such questions as “will my train turn up today?”, “will the railway be operating on the day that I want to travel?” and “is the government’s flagship rail policy dead or not?”. And the comparisons with W1A’s Director of Better were inevitable, but that’s because W1A was such a perfect parody of modern management that it’s true of half the senior roles advertised these days.

But among the jokes, nobody seemed to pick up on the fact that the role — full title, Head of Uncertainty and Scenarios — could be very influential in the nation’s transport policy.

Forecasts and targets

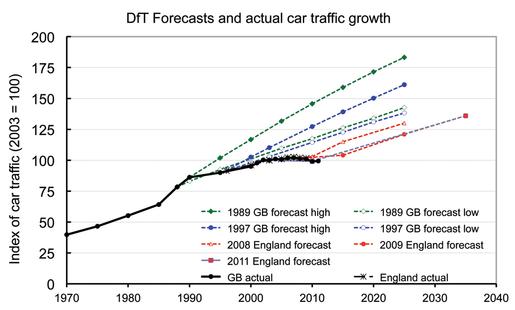

Ten years ago, the Department for Transport was notorious for its “hedgehog chart” of road traffic growth predictions. Every year for decades the department had confidently predicted an imminent rapid rise in the number of car and truck journeys.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, the policy had largely been “predict and provide”. A wonk would draw a chart showing an unquestionable rapid rise in journeys, so the government would respond by providing big new roads to accommodate it all. Councils demolished entire neighbourhoods, put up multistorey car parks, and enforced car-centric design in new neighbourhoods.

Meanwhile, the charts showed a sustained and undeniable decline in demand for public transport, so policy responded by curtailing investment.

But in the 1990s, in the wake of popular backlash against ever more destructive road projects and disillusionment from decades of false promises that they would deliver congestion relief, policy was forced to change direction. The “new realism” paradigm recognised that you can’t escape congestion by building roads. You have to enable more efficient alternative options if you want to break the spiral.

This is where the hedgehog chart era really takes off. The predictions of imminent rapid traffic growth kept coming every year, with unceasing certainty, but the traffic itself stopped materialising. Because first John Major’s government stopped building the roads for it, and then the alternatives began coming down the pipeline. Funding poured into the previously starved railways. John Prescott took control of transport in the early Blair years and supported urban public transport systems. And devolution in London enabled the rapid turn-around of the city’s long-declining public transport infrastructure and user experience, led by the Congestion Charge.

The influence of the new realism quietly waned over the course of the New Labour years, as our collective memory of why it rose in the first place faded, so when Cameron’s coalition government took over in 2010, predict and provide was ready to jump straight back in. And so the hedgehog chart era came to an end. The department made its usual confident predictions of imminent rises in traffic and it became a self-fulfilling prophecy once again.

Retrofutures and gadgetbahn vapourware

In a world of possibilities, creating a narrative of one certain future direction can have a powerful effect on policy that is difficult to resist. But creating a narrative of uncertainty can be a powerful force too.

In Traffic In Towns — the 1960s government-commissioned Buchanan Report on the future of road traffic — we were shown the future of road transport. Car and truck traffic would certainly grow immensely, and towns would need to be entirely reshaped around them. Small conservation areas might be preserved, but they would certainly need to be surrounded by dual carriageways, flyovers and car parks.

But amid all the certainty about our car-filled future, Traffic In Towns also reflects the 1960s narrative of great uncertainty about the future of transport technology. The report shows us a Parisian prototype monorail alongside Britain’s experimental “tracked hovercraft” — which “offers the possibility of very high speeds” and was cancelled and demolished just a few years after the report was published. Personal jetpacks and a cumbersome “air-cushion craft”, pneumatic tubes and “continuously operating chair-lifts” are presented as some of the wonderful possibilities in our unknowable future.

But Traffic In Towns explains that none of these imaginary modes presents any challenge to the “assured” future of the motor vehicle. Rather, they are reasons to doubt the future of the bus — which “does not appear to be the last word in comfort”.

Traffic In Towns has largely faded from public consciousness, but its companion — the other big 1960s government-commissioned report into the future of transport — lives on. The Reshaping of British Railways — the Beeching Report — told us that demand for rail is in inevitable decline amid uncertainty over whether it would have a role alongside the technologies of the future.

Uncertainty is an excellent impetus for inaction and driver of decline. Entire modes of transport have been dreamed up purely to impede investment in proven technologies.

Witness the discourse over investment in high speed rail in the UK and US over the past 2 decades. It might take 10 years or more to build a high speed rail line. Why would you set out to do that when, for all we know, rail might be obsolete by the time it’s finished? That’s certainly the narrative that the opaquely-funded libertarian think tanks have been trying hard to establish.

Self-driving cars, hyperloops, “autonomous pods” and gadgetbahns — often little more than vapourware, perpetually predicted to be “just five years away” from being possible — are never going to solve our transport problems. But they’re often not intended to. Their purpose is to cast doubt on investment now in proven modes of public transport and active travel.

Windows of possibility

We build narratives about the future, and our narratives, one way or another, build the future. We create scenarios and we assign them probabilities. We have windows of possibility, and we open or close those windows every time we call the future certain or uncertain. For all the jokes about the job title, the choice of who becomes a Head of Uncertainty, and the narratives the appointee shapes, might have enormous impact. Or not.