Gloucestershire lost out on funding in the latest round of DfT active travel grants. Instead of wasting everyone’s time appealing the decision, they should reflect on why.

So the Department for Transport (DfT) have been delivering on their promise to withdraw funding from any council-led active travel projects that don’t meet minimum design standards. Gloucestershire County Council (GCC) are reportedly appealing against one such decision. But the DfT were absolutely right to turn Glos down, and GCC should instead try to learn why. Let’s have a go at that together — there might be something we can all learn from their experience.

The inadequate facility

The proposal in question is for a cycleway along the route of the B4063 between the edge of Gloucester and the outskirts of Cheltenham (Google Map). It’s the old main road between the towns — many decades ago bypassed with a fast dual carriageway, but, as is the British way, always retained as a through route itself.

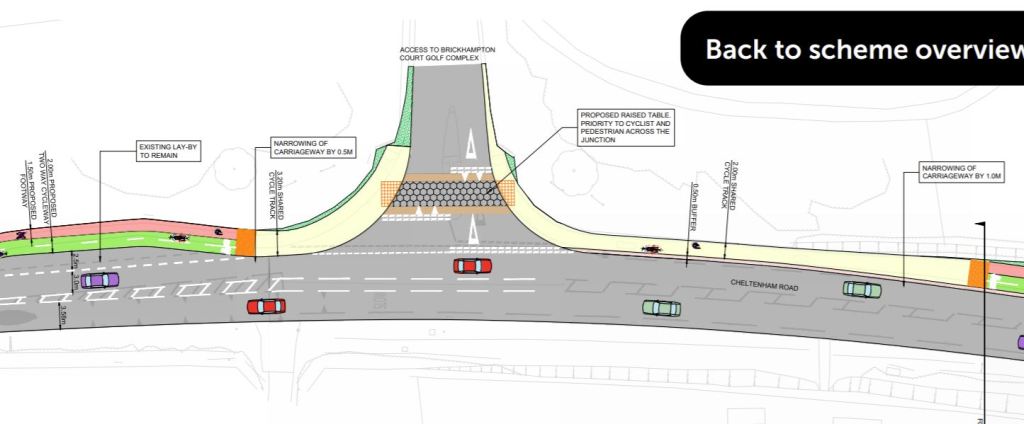

The plans (PDF) are a mix of cycle tracks — narrower than the design standards require — and shared use pavements, some of them as narrow as 2.0 metres, others with bus shelters in them. There are a few half-hearted attempts at priority crossings of side-roads and property accesses, perhaps an amateurish attempt to fool the DfT into thinking Glos have taken on board the modern design standards, but which instead stand out for their fundamental failure to understand the geometry of cycleways, as they attempt to bend the kerb-hugging cycle track around the vast splays of the side roads. Of course the DfT’s feedback described this as “inadequate”. The DfT’s claim to be turning down councils who waste funds on crap facilities would have zero credibility if they’d given money to this rubbish.

The way to fix this is screaming out from GCC’s own annotations on their designs. They say things like “existing layby to remain”. They mark multiple turning lanes for stacking motor vehicles at signal-controlled junctions. They retain bus stop laybys — deciding that allocating the limited available space to motorists so they can easily overtake buses is a higher priority than allocating it to designing the cycleway well. In a stretch where they deemed there was sadly not enough space to separate cycling and walking, providing only a 3.0m shared pavement, they mark on the adjacent carriageway 3.32 metre wide central hatching!

As the DfT feedback says: the space is there, the council just need to show the political will to reallocate it from motor capacity — on a road, remember, that has already been bypassed by a high capacity parallel route.

Are there any critical fails?

Extensive use of shared use paths in inappropriate areas, poor and indirect provision at junctions. Could seek to maximise pedestrian and cycling space through carriageway narrowing etc. …

Designs as shown are heavily motor centric and could provide higher quality cycle and pedestrian infrastructure in line with LTN 1/20,(e.g. indirect crossings, no side road priority and so on). Optional aspirations marked on the drawings provide suitable interventions, however the design approach presented could have shown greater ambition to address carriageway space and motor capacity/dominance.

The DfT are saying: be bold. Forget motor capacity, that’s what the bypass is for. Design a fantastic cycling and walking route, and then see what you can fit in for motoring around that. Can’t fit in a proper 3.5 metre cycleway with separate 2 metre footway and fit in 2 motor traffic lanes? Then don’t fit in 2 motor traffic lanes. Have a single lane pinch point with one direction of traffic giving way. Put in a bus gate to remove through private motor traffic if you have to. There’s no shortage of ways you can make this road great for cycling and walking, you just need to accept that the cycleway is a higher priority than the central hatching on a road — I don’t think I can say this enough times — that is already bypassed by a high capacity parallel route.

Sympathy for the councils

It’s hard not to feel just a little bit of sympathy for GCC. For decades they’ve been told to design rubbish, and suddenly they’re being chastised for it. They’ve got a highways department conditioned to expect cash for any old crap, and suddenly they’ve been told they’ve actually got to work for it. The reality of the situation must be terrifying — no wonder they’re in denial. If the DfT really are going to keep up seriously enforcing the new standards, it’s going to be quite the rude awakening for those councils who have found active and sustainable transport funding an easy target for something they can use to keep their highways departments busy, or covertly channel into motor-centric schemes.

You can also perhaps feel a little sympathy for a council that has designed something that, until the introduction of LTN 1/20 just six months ago, was largely what the government’s own design guidance was telling them to do. The designs GCC submitted are classic LTN 1/08 stuff.

Most of all though, I felt genuine sympathy for GCC when I read in the news coverage that the designs were largely drawn up for them by Highways England — an agency of the Department for Transport.

In 2013, Highways England committed to “cycleproofing” the interfaces between their network of motorways/trunk roads and the local road network, and said some genuinely encouraging things about what they do to overcome the severance caused by their roads and junctions. Alas, the sense I get is that policy effectively died long ago. (It’s a fate that awaits many policies: the people who championed it move on in their careers, those who are left to implement it aren’t enthusiastic enough, empowered enough, or qualified enough to make it live up the original vision or to then push it through to its next phase, and so it withers.) The B4063, it seems, is Highways England’s solution to cycleproofing the A40 — that high capacity route which bypasses the B4063 — and its junction with the M5.

From GCC’s perspective, they’ve submitted the DfT’s designs to the DfT for funding and the DfT have come back and said they’re not good enough.

How much initiative would you like us to use?

In their feedback in the designs, the DfT make it clear that GCC should be bold and use their initiative:

B4063 could potentially be more than a local distributor road as the A40 provides a bypass to this corridor and access toward the city centre via roads with more overall highway width available for corridor improvements; there are clear opportunities for network level interventions to help progress more ambitious schemes on the local road network

They’re saying what I said above: if they need to find more room to do the cycle track properly, GCC should take away central hatching, turn lanes and laybys. They should make traffic wait behind the buses at stops if necessary. They should put in single lane pinch points. If it comes to it, filter out through private motor traffic. If there’s too much traffic, enable modal shift and send any remaining excess elsewhere.

The problem is that GCC are at the same time being told not to do that. Mid way along the route is a large industrial estate, which continues to grow. The B4063 therefore has to be a distributor road — it’s the only available route for HGV traffic to service that industrial estate. The council are obliged to accommodate HGV access.

It’s hardly surprising that GCC’s highways department are rather attached to all the turning and stacking lanes at junctions along this road. They’ve spent five decades incrementally producing these motor capacity “improvements”, one by one, as and when developer contributions from housing and industrial estate expansion allow, as central government guidance has advised them to do. As central government still advises them to do. It must be exasperating to be told to fix these mistakes by the same government department that had told you — is telling you — to make them in the first place.

Ideally, perhaps, the industrial estate wouldn’t be where it is. It would be alongside the A40, or the A417, so HGVs could hop straight onto a main road without having to wind through villages on a road shared with cyclists and local buses. But it’s not, and in the past decade central government have been further eroding what little power local councils and local people have to determine where developments like these happen in their areas.

Perhaps, when the DfT say GCC should be ambitious and seek “network level interventions”, they are inviting GCC to bid to the Active Travel Fund for funding to build a whole new HGV access road direct from the industrial estate to the A40 that will enable through traffic to be removed from the B4063?

So I have some sympathy for councils, even the ones who still haven’t got it on active travel. GCC should go back and revise their B4063 plans, they can do much, much better. But they are given all of the responsibility for delivering on a central government vision and none of the power. They must juggle the demands of multiple, contradictory instructions and policies from different branches of central government — even from other teams within the same department.

On balance, at this stage in the Active Travel Fund it’s a good thing that the DfT are micro-managing the bids to prevent the money being wasted. But if this is ever to scale up to something that really delivers for active travel, central government need to fix their own policies that push councils to keep preserving and reinforcing motor dominance, and then empower the local authorities who are expected to do the work.