On The Scotsman, Grant Kavanagh, owner of a print shop on Leith Walk, pleas for space on the street to be given not to proper cycling infrastructure but to more car parking. These are Kavanagh’s arguments:

Parking on Leith Walk is a real problem for businesses at the moment and it’s really a case of motorists bringing a lot more business than cyclists.

Everyone who lives and works on Leith Walk wants it restored so that we can encourage people back into the area. If people cannot park then they will not come down to Leith Walk and that will not help us at all.

There is a vast difference between the number of vehicles that pass down Leith Walk in comparison with the number of bikes, so I don’t understand the need for dedicated lanes for minority road users.

I don’t think I need to address that last claim — about cycling infrastructure being for the minority who are Cyclists — so soon after writing about it at length. It’s the earlier ones that merit a further look.

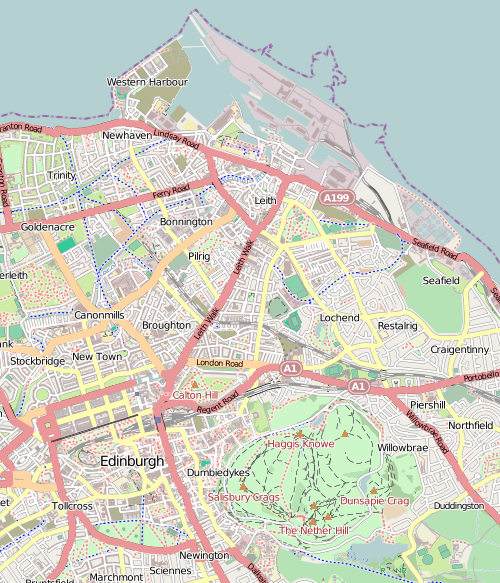

Kavanagh clearly believes that the businesses on Leith Walk are, or are capable of, attracting customers from all over Edinburgh, who drive in and park up to shop. His belief is quite typical of small retail business owners. We have developed a national myth about the importance of motoring and car parking to urban retail. I’ve written before about how this myth was explored a few years ago on Gloucester Road in Bristol — a road which shares important characteristics with Leith Walk, namely, being an arterial ‘A’ road, running through a densely populated residential neighbourhood, and being lined with small independent businesses and a few convenience stores.

The shopkeepers of Gloucester road were asked to estimate what proportion of their customers came by car. The average answer was more than two fifths. But actually only just over a fifth drove to the shops. They greatly underestimated how many people walked, cycled, or took the bus. Their estimates of how far their customers were travelling was also way out, with business owners believing that they are able to attract customers from miles around — just as Kavanagh does — when in fact most lived a short walk away. And they found little to support the idea that motorists were good customers, with drivers likely to rush in and rush out while pedestrians hang around and visit several different establishments.

Mr Kavanagh’s business is relatively specialist. His is not the only print shop in Edinburgh, but perhaps it is the best quality or best service or best value or for whatever reason he really is able to attract customers from all over the city and beyond. But, and I hope the business owners of Leith Walk will not take this personally, very few of the shops on the street are. I don’t believe that anybody is going miles out of their way to go to a Co-op, a post office, a pharmacy, a bakery, a kebab shop, Tesco Express or their barber, accountant, or solicitor. It should not be taken as a slur on the reputation of the perfectly nice delis and coffee shops to state that almost all of their customers come from no further away than the office buildings a couple of minutes up the road and the tenement blocks around the corner, for this is the nature of delis and coffee shops everywhere.

Leith Walk succeeds as a local high street because its shops and services are mostly local shops and services — the sort of essentials that everybody needs but nobody wants to have to go out of their way to obtain. Which is why I am fairly confident that if you surveyed the people who shop there, you’d find that most live locally and walk, many combine walking with the bus, more than Mr Kavanagh would expect cycle, and a lot fewer than he would believe drive (or ever would drive, however much car parking was provided). My guess is that of those who do drive, a very large proportion are making a journey of just a couple of kilometres — for we know that a large proportion of urban car trips cover very short distances — and that Kavanagh would again be surprised at how many would consider leaving the car behind — indeed, would be relieved to be able to do so — if they were to be given a viable alternative like safe and comfortable cycle tracks. And that would mean fewer local folk clogging up the parking spaces as they stop to spend 89p on milk, and more spaces for those who are driving in from miles around to spend big at the print shop.

But we don’t have to argue over our guesses. Why not test it? The methods of the Bristol study were simple enough, and it might take one person a weekend to replicate, or a small group could do it in an afternoon.