So the government is looking into some form of privatisation of the motorways and trunk roads that are still under their control — that is, the English Highways Agency network.

It sounds radical, it sounds like it could be frightening, it sounds almost like a parody. Actually, it’s boring. It’s probably even more boring than the familiar private roads like the M6 Toll and all our big motorway suspension bridges. It will probably turn out to be about as boring as the management of motorways and trunk roads in Scotland, where private companies manage and maintain the roads using railways-style regional franchises. You’ll know them by the names and emergency contact numbers plastered over the countryside on massive signs, but otherwise, the difference they make to the road user is entirely hidden: the roads are still toll-free and they’re still full of potholes. As far as I can tell, the main purpose of this kind of “privatisation”, like with Network Rail, is as a quick way of fiddling the accounts on the national debt. The extra billions that these things inevitably end up costing taxpayers are apparently worth it for the extra tens of billions of borrowing being kept off the national books, so that George Osborne can appear to be on trajectory for his arbitrary debt reduction target.

I wouldn’t worry too much about any implications for cyclists. England’s trunk roads network is way beyond the stage where anybody would dare cycle on it. We’re talking about motorways and motorways in all but name.

Where things might matter is with the prime-minister’s suggestion that privatisation might allow large-scale road construction programmes to recommence, with the idea that companies who build new roads could collect tolls on them capturing the headlines. It would be a shame if this happened. The Tories should try to think back and remember why they abandoned that approach last time.

But do we actually have to worry about a return to large-scale motorway construction led by private investors? I not sure we do. Quite aside from the many reasons that forced the Tories to abandon that unpopular policy last time around, I can’t imagine the private sector wanting to invest in a dying technology.

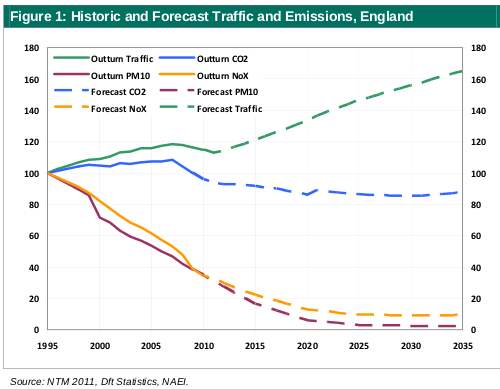

Local Transport Today reported this week that, despite private motor vehicle use in London being in near constant decline for thirteen years, the Department for Transport are standing by their prediction that in two decades time, traffic in London will be a whopping 43% above 2010 levels. Similar predictions are made for the rest of England, with 44% in the country as a whole. Given the exodus of young people from learning to drive, who do they think will be driving this traffic in the mid 2030s? What technology or fuel are they expecting to be an affordable means of powering all this traffic? Where do they think it’s going to go? This is the city whose streets are famously “too narrow”, whenever you propose giving some street space to something other than private motor traffic, but which apparently have room spare for 43% more of that.

What purpose could such absurd and crudely fantastical forecasts of traffic growth and confident rejections of the idea that motoring has peaked and is passing have? Is it perhaps meant to be the prediction in a predict-and-provide programme? Or is it less a prediction and more an ambition, for this greenest-ever-government? Are they pining for The Great Car Economy?

It’s true that car use fell in tandem with the economy, but if we want to stop the plummeting economy, we have to come to terms with the fact that both falls are merely symptoms of the fact that the cheap fuel that powered both cars and economy is a thing of the past. The lines on that graph simply aren’t possible these days.

Whatever. I can’t see private investors having such confidence in roads as a growth market that’s worth putting their money in. Unless someone can give them plausible answers to the questions like “by the time the road is built, who will want to drive on it?” and “how will they power their vehicles, and how will they be able to afford that?”, I’m not sure they’re going to want to take the risk on a the basis of a made up graph.

This quite aside from experience with the M6 Toll Road, whose operating income still doesn’t, and didn’t even during the economic boom times, come close to paying off the annual interest on its construction costs, despite attempts by the road’s owners to encourage new development around its junctions. Turns out that, despite their moaning, most people are quite happy to sit in traffic jams on the old roads if it saves a few quid on the toll.

But there is potentially another reason why Cameron might want to offload our motorways, beyond fiddling the national debt or encouraging new construction. The old Severn Bridge is falling down. The Scots are spending £790 million replacing the Forth Road Bridge (though nearby infrastructure projects suggest that the final bill might end up at £7.9 billion). Who knows how much the emergency repairs to the Hammersmith Flyover will end up costing London? The main motorway and trunk road construction boom began in the late 1950s, and a big chunk of engineering is about to reach the end of its design life, corroded and crumbled by rock salt, ice and billions of truck movements. What if privatising the motorways is just preparation by central government for distancing themselves from the difficult decisions of whether to repair, replace or abandon our collapsing concrete highways in the sky?

As your article points out, Joe, the fundamental reasoning behind the consideration of ‘privatising’ the strategic road network is to remove the debt and borrowing associated with improvements from the Government’s balance sheet. The costs are still, ultimately, met by the taxpayer through regular payments to private companies, but this does not matter too much in terms of the figures on the balance sheet, even if it does cost more for taxpayers in the end. As a colleague of mine once said, its an accounting trick, and little more.

With regards to the outputs of the National Transport Model, it is right to question the underlying assumptions that the model uses to create the forecast figures. The impacts of things such as social media, changes in attitudes towards cars, and changes in lifestyle have historically been difficult to model, and the ideas of peak oil and peak car are still far from widely accepted in transport planning circles (though an increasing number are). It is also worthwhile considering the numbers produced in the round. For example, whilst traffic in London is forecast to grow by 43%, the proportion of traffic travelling in very congested conditions is due to rise to 42% (from 24%). So while more traffic is being processed by the network, its at a slower speed.

It is also worthwhile noting that the model results are not necessarily a statement of policy. Model results should be one of a number of factors involved in decision-making, and the strengths and weaknesses of the model in question need to be factored into this. Something to note here is that the National Transport Model is a very strategic model, and therefore a more localised model for London should ideally be considered as a (slightly) more accurate forecast for the capital.

Keep up the good work on the Blog!

There’s one big, big problem with the privatisation strategy –

Once you’ve promised an income to the leaseholder based on the number of cars using the road, either through real or virtual tolls (which is not unusual), you lose the ability to manage congestion and pollution through independent road pricing.

Clearly, this should be reason enough not to implement the strategy…

I’m not sure the problem is quite as you portray it. The reason car use has grown steadily in recent years (and may well return to the trend level of growth) is precisely that the link with oil use has broken. Cars have got much more fuel-efficient and hybrids and so on are continuing that trend. At the same time, car prices have fallen. So cars are steadily becoming an ever-better bargain against public transport and cycling (which still costs something, even if it’s excellent value).

The problem is consequently that all the current anti-congestion measures are targetted at fuel duty and so on but ever less fuel is getting used.

As cyclists, we should, I think, be fully in favour of a national, distance-based scheme to charge for road use (with higher amounts at the busiest times). That would encourage people out of their cars at the busiest times, cut the cost of driving for people in the least congested areas (where public transport is worse) and make it explicit that the problem is congestion, and the space all cars (petrol or otherwise) take up on the road.

Privatisation isn’t, I think, just a trick. Private companies do behave differently. I don’t mind if roads are handed to a well-regulated private company. But it is absolutely vital, as Fred argues above, that any privatisation now not end up precluding the introduction of a rational charge for road use for the vehicles that take up the space (pretty much everyone except cyclists).

Invisible Visible Man

http://invisiblevisibleman.blogspot.co.uk/

A national distance based scheme to charge for road use does raise the possibility that future cyclists may find themselves fighting for roadspace with drivers whose sense of entitlement has been greatly heightened by the fact that they are paying, say, a pound a mile while bikes are paying nothing. I can imagine the bitterness and anger that many white van men will feel.

Don’t you think it matters then, that: “England’s trunk roads network is way beyond the stage where anybody would dare cycle on it.”? Surely those roads should be right at the front of the queue for segregated facilities, since they very often provide the only route from one place to another?

One way to shift the balance is to have an incentive for private road maintenance companies to provide infrastructire, say a 1% drop in subsidy year-on year unless there’s a measured increase in cycle use: that way they would have an incentive to invest in good cycling infrastructure (which is about 1% of roadbuilding costs) and encouraging cycling.

I don’t think a national, distance-based system would worsen the problems. It would make explicit what the charges cover (use of road space, damage to the roads and pollution). Bikes impose none of these costs. The current confusion reflects the lack of clarity about what fuel duty and vehicle excise duty are meant to do.

http://invisiblevisibleman.blogspot.co.uk/