While London’s attention is turned to Blackfriars Bridge, those blissfully unaffected by the bumbling buffoon Boris* might like to take a look at the 45 proposals that councils around England have submitted to the DfT’s Development Pool in the hope of being picked for a share of the current £630 million available for local transport projects.

Heads of council transport departments and engineering consultancies have dusted off the bypasses, relief roads, distributors and links that they have been drawing and re-drawing, submitting and resubmitting for funding for fifty years.

Look at your local area in the Development Pool and you’ll find them all there. They’ll be called something like “town centre improvement”, “bus rapid transit”, or “cycle route enhancement and congestion relief package.”

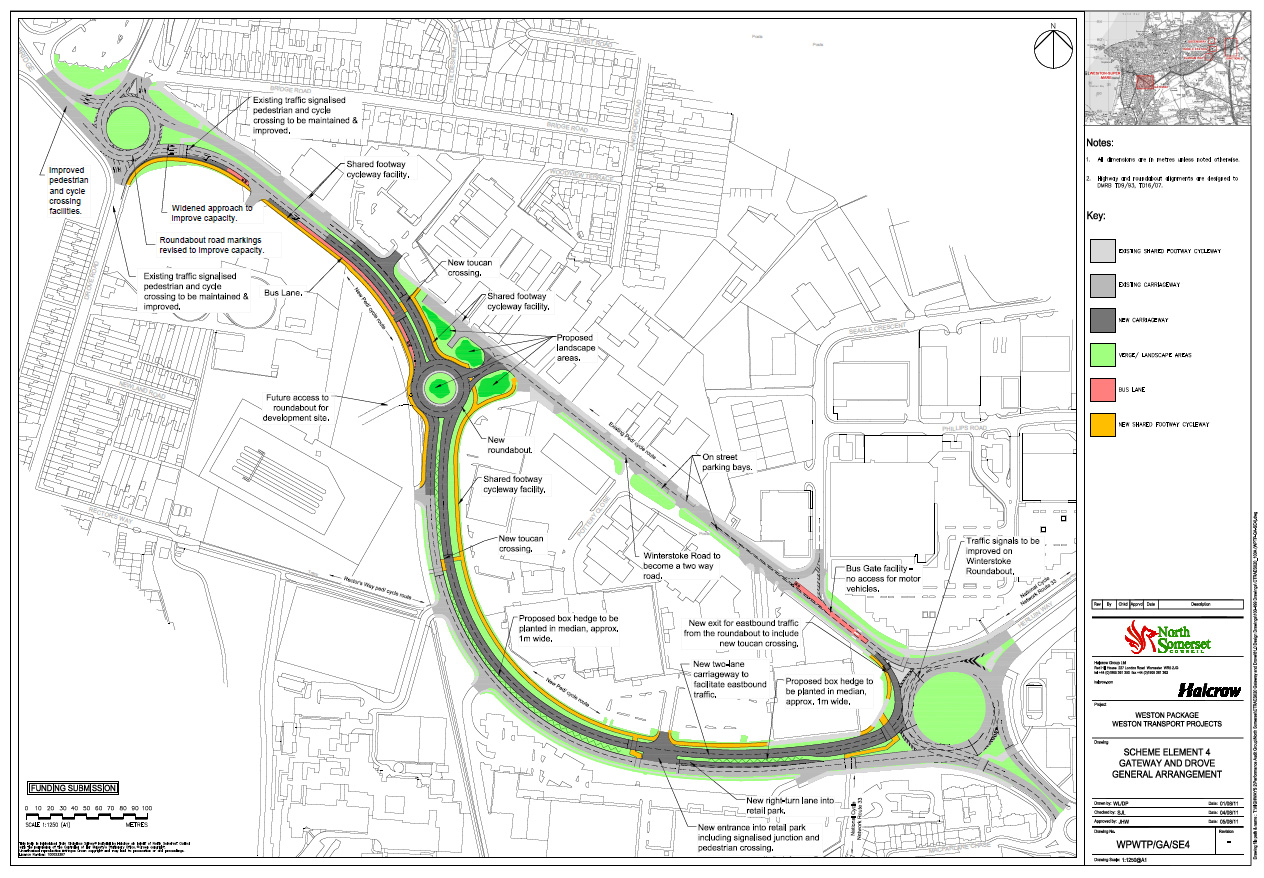

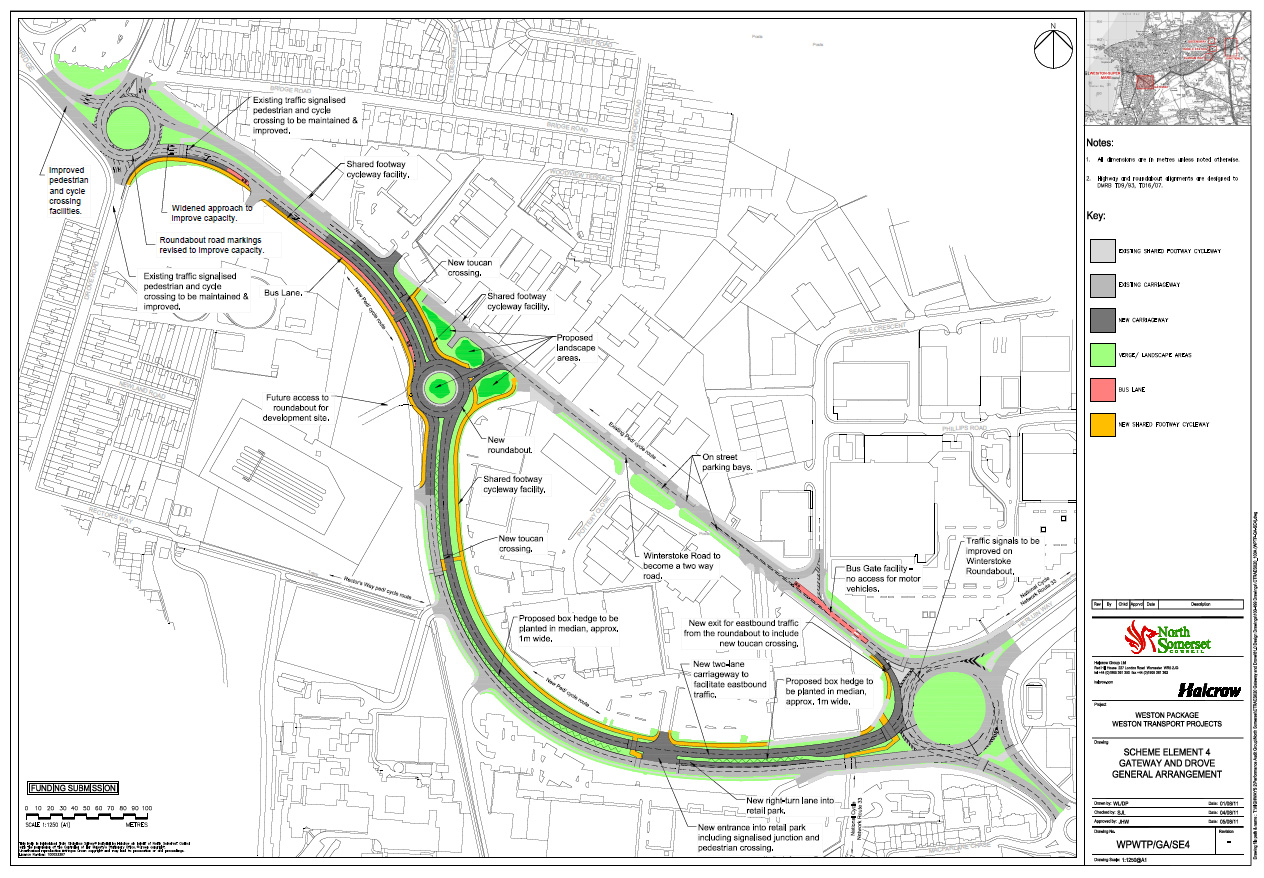

Things like the Weston-super-Mare package, which will provide better bus services and enhanced cycle routes, by, erm, widening town centre roads and ensuring that they have substandard and probably unusable shared pavements alongside.

Of the Cross Airfield Link Road, proposed to open a large brownfield site to light industrial and retail developments,** the Weston package says:

The approval is for a single carriageway road 2.4km in length, four roundabout junctions and parallel shared-use foot and cycle ways. The proposed road is 7.3m wide single carriageway. A 3.0m wide segregated shared pedestrian and cycleway will be provided along the northern side of the new road with a 3.0m footway along its southern edge. Both the cycleway and the footway will be segregated from the carriageway by 5.0m verges which are to be planted with trees to create a boulevard along the road’s length. The scheme design includes Toucan crossings in strategic locations.

This sort of stuff should be illegal — I mean that, actually legislated against. Proposing a shared pavement as a transport route in a built-up area should mean automatic rejection from the Pool, pending a suitable revised design. Three metres should be the bare minimum width requirement for a two-way dedicated cycle track on busy roads like these, where large trucks are expected, and even then the council/agency should have to provide a very good explanation for why a 4.0m track or a pair of 2.5m unidirectional tracks would be unreasonable. Weston are proposing to spend our money on a future facility of the month, and that should be against the law.

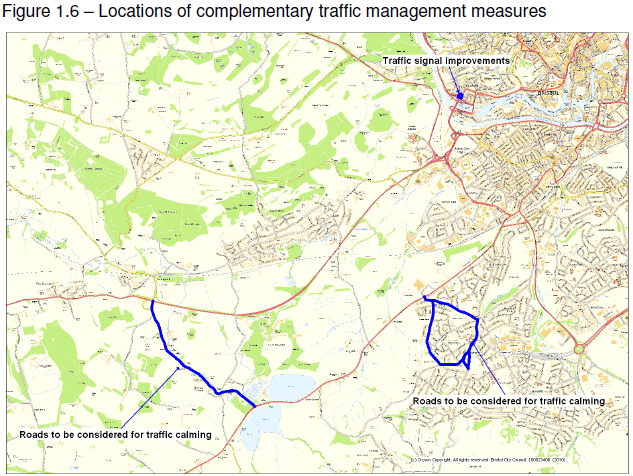

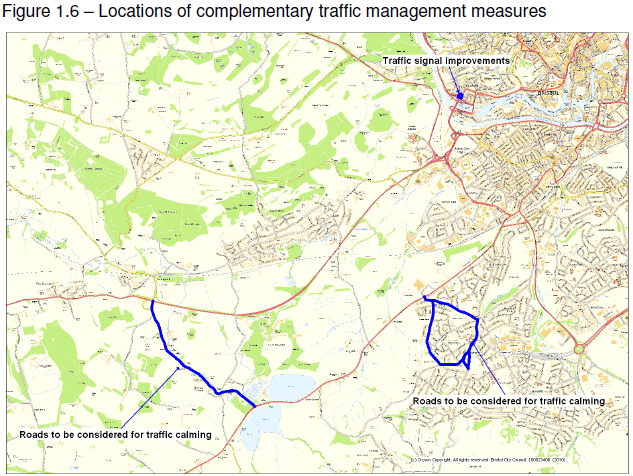

There is a pattern to the Development Pool proposals. Another Westcountry project is the “South Bristol Link”. It’s a Bus Rapid Transit route, and definitely not the South Bristol Link Road, the extension to Bristol’s southern bypass that the council has been drawing and re-drawing, submitting and re-submitting for funding since the sixties. It just happens to be a road, and to follow the route of the South Bristol Link Road. But it has bus lanes, which makes this a Bus Rapid Transit project, and definitely not the same old bypass. Bristol has grown since the road was first proposed, but the route was set aside, leaving a strip of undeveloped land surrounded by housing. Here’s the artist’s impression of the Bus Rapid Transit system:

Look at that lovely 3.0m shared pavement — in this case divided into equal shares of 1.5m footway and 1.5m bidirectional cycle track. Doesn’t it look so inviting, riding against traffic, alongside the car parking bays, in a space barely wide enough for one bicycle. One bicycle is presumably all that the council are expecting: there is no provision for two bicycles travelling in opposite directions, or travelling in the same direction at different speeds. The council will no doubt seek a solution to that problem if and when it ever arises.

It’s a classic British road mockup. Hide all the cars and clutter and put unnaturally large pedestrians and cyclists in the foreground. The road would be carrying thousands of vehicles per day, swelling with induced demand, but here it’s all free flowing, and just a single homeowner parks a car in their neat free parking bay, gift from the council. Perhaps all the other cars are parked in the city centre because neither a 1.5m bicycle track nor a bendy bus to an edge-of-town park and ride interchange are attractive methods of getting to work?

A 1.5 metre bicycle track will be of no use to anybody. The parking bays will, if you let them, fill with second and third cars, and spill out over the drop kerbs and green spaces. Within a few years the city will discover, to everybody’s surprise, I’m sure, that there is limited demand for a bus between suburban housing and an edge-of-town park and ride interchange, and the bus lanes will quietly be turned into general traffic lanes.

I’m really quite embarrassed for Bristol, having praised them for exceeding our (low) British expectations on Redcliffe Bridge. Seriously, what the fuck, Bristol? “The country’s premier national and international showcase for promoting cycling as a safe, healthy and practical alternative to the private car for commuting, education and leisure journeys.” Bristol’s “cycling city” status clearly hasn’t really sunk in for the highways engineers, who plainly have no experience of cycling or how to provide for it, but who confidently give it a go anyway having read something once in an instruction book.

The city council are cutting hundreds of jobs, and I think I’ve spotted where a few of them of them could go.

While cutting those jobs, the city is seeking £43 million for this bypass Bus Rapid Transit line. I think the Cycling City team could use the money far more profitably, retrofitting the city’s existing big roads with wide, fast, direct, prioritised, attractive tracks, and could never support Bristol throwing the money away on the South Bristol Link. But even for an urban road project, and even leaving aside the contemptible crap cycle facilities, this is an especially bad scheme. The one potential benefit of a bypass is to have a designated road on which to push traffic from city streets. But to capture that benefit you have to reclaim those city streets immediately — make it unattractive to drive on them for anything other than essential property access and loading — otherwise people will just find new ways to fill the old streets with more ridiculous car journeys. With a southern bypass Bristol could close ratruns through the southern suburbs; take back space on the main southern arterial roads — the A38 through Bedminster, for example — for the pedestrians and cyclists who spend more money in the shops along them; it could even close some more of the inner ring road. Bristol failed to capture those benefits when it previously built big bypass roads, on the northern and eastern fringes, and it would fail to capture any potential benefits of a southern bypass, proposing to make it a little bit less attractive to drive only on a couple of residential streets and a country lane:

Take a look at your local schemes on the map. There are potentially worthwhile projects in the pool too, like rail upgrades and even reversing railway closures. More has been written about the bids by Sian Berry and George Monbiot. The DfT are soliciting comments on development.pool@dft.gsi.gov.uk, deadline TOMORROW, Friday — though I’m not sure why, and whether anybody will ever read them.

* but we’re all affected, sadly, due to London’s unfortunate influence over the nation.

** it’s actually one of the least indefensible of the new roads, and one of the least bad sites for such developments, being on brownfield located alongside a railway and within walking and cycling distance of the town’s population and railway stations. I’m sure they will fail to make good use of all that potential, but it’s still progress over road-only out-of-town greenfield sprawl.