This popped up in my Tweetdeck saved searches column:

It caught my eye because I’m quite ready to be critical of Bristol. And I will be.

But first, some reassurance. These numbers are (a) just a levelling off after years of growth, (b) probably not representative of the real situation in Bristol, and (c) probably a load of rubbish.

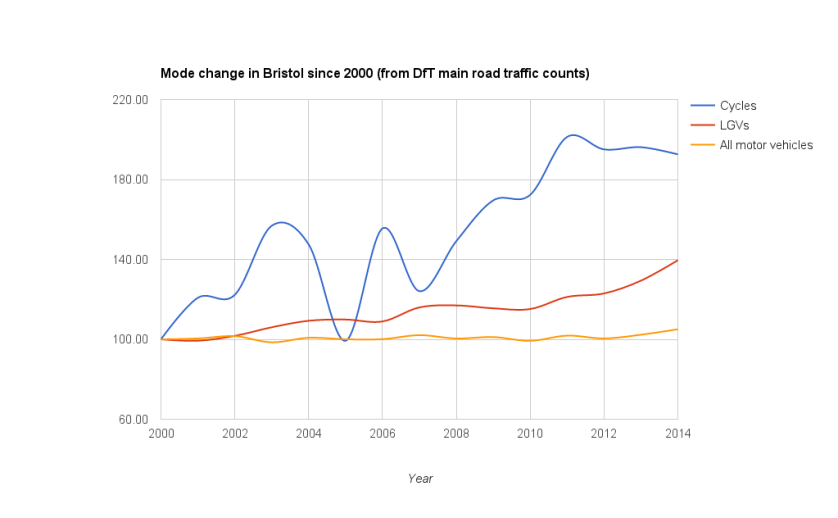

The numbers come from the Department for Transport. Here’s how they look when plotted as an index relative to 2000, alongside motor vehicles (beware, truncated y axis):

So this “decline” should be seen in the context of cycling journeys still being higher in number than in the last decade.

But actually this probably isn’t the right data to even tell you whether there has been a levelling off. You might get a clue from the fact that this data puts cycling’s mode share at 1-2% in a city that claims several times that much cycling.

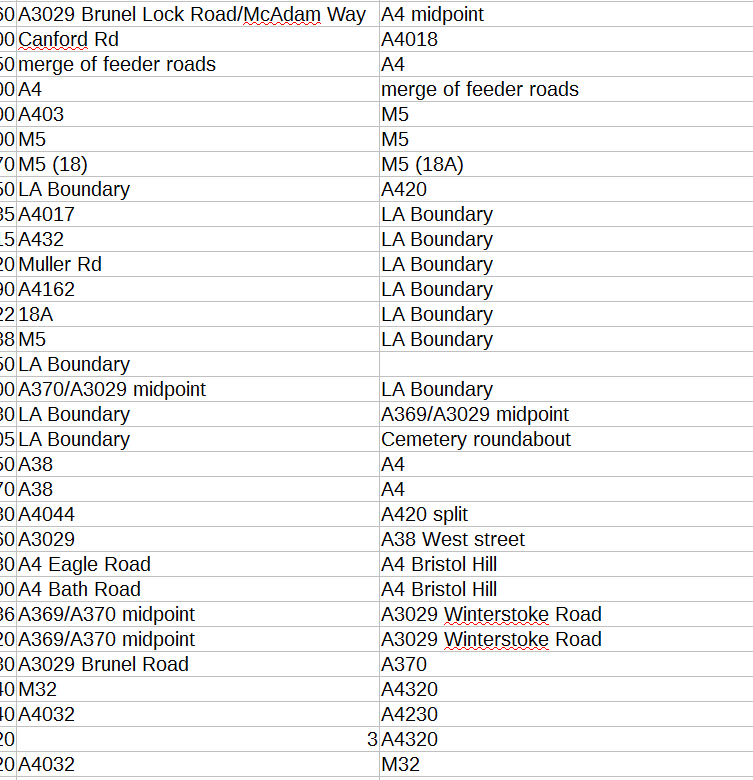

It’s because this is Department for Transport traffic count data, and the DfT only count on main roads. Roads like these:

The biggest, busiest and fastest roads in the city, including several where cycling is not even legal.

But Bristol’s strategy for cycling has largely neglected the main roads. (That is itself one of my criticisms of the city, but we’ll get to that.) Bristol’s rise as a cycling city is built on the foundations of its off-road routes on post-industrial corridors — the Railway Path, harbourside, greenways and towpaths. And in recent years its main policy developments have been slower speeds and filtered permeability on residential streets and in the city centre, as well as the development of additional joined-up off-road arterial routes.

So one could almost hypothesise that a fall in DfT main road traffic counts are what you’d expect to see in a city where the policy has been about creating alternative routes to the main roads.

Finally though, even for the dataset that it is, these numbers need to be taken with a big pinch of salt, because they are DfT traffic counts. The clue is in the fact that the line for cycling is really all over the place. These are based on a single day per year sample, probably collected by folk sat by the side of the road with pencils and paper, and so subject to big sampling noise.

That doesn’t mean Bristol’s doing alright

In 2012, we took the Cycling Embassy to Bristol to admire the Railway Path, the Living Heart Campaign for city centre filtered permeability, the then newly completed Concorde Way arterial route and the harbourside. Since then there have been some developments.

Bristol had just voted to replace its ineffective council-led model of local government with the mayor-led model, and there were high hopes that the city might start seeing some progress after years of plodding along. Hopes were higher still when independent George Ferguson was elected later that year with a mandate for improving cycling in the city. Ferguson’s policies even promised to finally start addressing the main roads, and thanks to the volunteer-run Bristol Cycling Campaign, there’s even a network plan ready prepared to work through.

So three quarters of the way through his term, what have we got?

The Baldwin Street cycle track and the Clarence Road cycle track (2 years late and with the council instantly pandering to incompetent motorists by reducing its defences). Two very welcome schemes. But that’s three years for a kilometre of tracks, not even fully connected to the wider network. At this rate it will take centuries to complete the network.

But far more worrying than what hasn’t happened is what has. Bristol is still designing crap like this — and building it, despite the countless warnings they’ve received:

Busy, narrow, discontinuous shared use footways of the kind that should have been consigned to Crap Facility of the Month 15 years ago. This is not the stuff of a “cycling city”.

Bristol is still doing far better than — and doing nothing quite so embarrassing as — the likes of Birmingham or Leeds or Manchester, of course. But that should go without saying. That should go without saying. Bristol is expected to be better than Birmingham and Leeds and Manchester. But it’s certainly not exceeding expectations. It’s not moving forward or graduating from the low-hanging fruit of greenways to the hard work of fixing main roads. When London is building the NS/EW superhighways and many more kilometres of good stuff besides, nothing Bristol is doing looks exciting anymore.

And I think that’s because Bristol doesn’t appreciate what it has got, or understand how it got it. It has fallen for its own myth that it is an alternative city, and takes it for granted that the cool, green, self-reliant people of Bristol have a cycling culture. In fact, that culture arose alongside its off-road routes, and it could disappear just as quickly.

Worse even than the crap facilities on new roads is closing the Ashton Bridge for a year, severing greenway routes, to build a busway — diverting anyone who is left willing to cycle onto a dual carriageway. Or closing the Railway Path for months with similarly inadequate diversions. Over the past few years the city has variously proposed destroying the Railway Path entirely, destroying the riverside “chocolate block” path, and destroying part of the harbourside, all in the pursuit of mediocre bus systems serving the outer suburbs.

It is clear that council officers in the city have no appreciation of how absolutely critical these kinds of routes are — how dependent the growth in cycling modal share has been on them, how much they contribute to the city’s mobility, and how easily and how totally the city can be set back by allowing such routes to be destroyed. But outside the council there’s a complacency too. I don’t think many people quite appreciate just how critical the harbourside routes are, for example, because they exist by default as spaces left behind by industrial decline, rather than as something that had to be fought for, paid for, planned, designed and built. Yet they tie together the city’s radial routes in the centre — a vital function that other cities can struggle with immensely.

Bristol is still far better than Birmingham or Leeds or Manchester. But it’s not radical. And it needs to start taking its cycling infrastructure seriously. Because mode share can go down as well as up — and the fall can be faster than the ascent.

Reblogged this on CycleBath and commented:

What is interesting about this is where the DfT measure cycling. If a similar approach is used in BaNES, as better quality off-road and quiet-way cycle infrastructure is developed, cycling will be perceived to drop, even though it is increasing.

Nails soundly hit on their unknowing heads.

The suppressed demand for cycling in Bristol remains powerful ,while the obdurate refusal of motorist interests to allow adequate supply is blind, dumb and lurking in every decision making arena. (The ghost of Osborne’s Minimal State is a further drag on progress). The resulting hiatus is worrying.

Another limiting factor is the misguided devolution of responsibilities (if not powers to do anything positive) to Neighbourhood Partnerships whose budgets are tiny and whose active members are entirely unrepresentative and unaccountable). Transport cannot be managed from the bottom – a wide view and a long-term strategy are vital.

However, we are in the lead up to very important elections in the Spring – every Council seat, the Mayoralty AND the Police and Crime Commissioner’s job (the incumbent is a cycling sceptic) are up for election this time. A renewed Space 4 Cycling campaign might help – but more voices and more actions are needed. Time to wake up Bristol – all we have won could be lost.