The Mayor is giving boroughs money to build Quietways for cycling and the boroughs are misappropriating it. Exactly as history told us they would.

My commute these days takes in a section of the Mayor’s new “Quietway 3” as I go an extra mile trying to avoid as much as possible riding on the roads of the City of Westminster, one of London’s 33 local government boroughs.

Although TfL has been advertising Quietway 3 as “complete” for some time, it’s only in the past few weeks that barriers have come down to reveal the first physical hints of its existence.

Filter bubble

At Boundary Road, on the Westminster/Camden border, the Quietway crosses the busy Finchley Road, the main arterial road to the M1. The Quietway here benefits from a mode filter which prevents through motor traffic on Boundary Road from crossing the Finchley Road.

A filter has existed here for many years already, built as part of a route in the failed London Cycle Network. But for the Quietway, it has been expensively rebuilt with a very slightly different alignment, and with a replacement set of traffic signals that include low-level cycle signals.* The only thing that is really new here, and which is highlighted as one of the big boons for cycling, is an additional banned turn to further filter motor traffic from Boundary Road.

Less prominently highlighted is the other big benefit of this banned turn, which reveals the real reason for the existence of this mode filter. The new banned left turn means that traffic on Finchley Road doesn’t need to be stopped for pedestrians to get a green man signal across Boundary Road. Like the LCN-era mode filter before it, this scheme has been designed to smooth and expedite traffic flow on a major arterial road by removing potential junction conflicts and minimising its red signal time. It is a motoring scheme dressed up as a cycling scheme in order to use up a cycling budget.

Signal failure

Elsewhere the evidence of Quietway 3 is even less forthcoming, but we can see from the consultations what is planned.

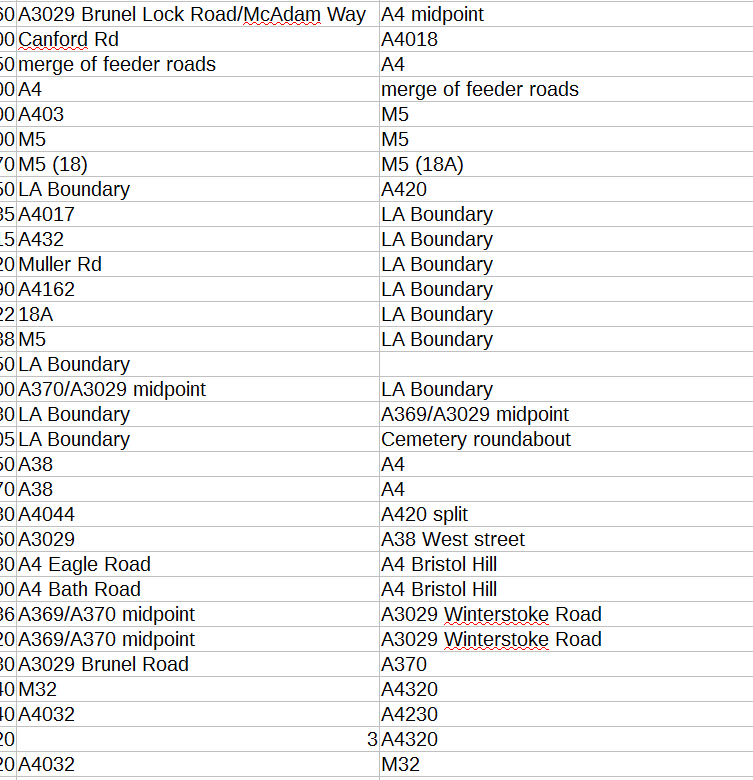

After Boundary Road, the Quietway heads into Westminster borough on Ordnance Hill. At times when the parallel Finchley and Avenue Roads are busy and congested, Ordnance Hill becomes the motorist’s ratrun of choice for racing to Swiss Cottage, and it’s crossed by a series of other popular ratruns. So what are Westminster proposing to do to transform this busy motoring racetrack into a Quietway that can deliver on the mayor’s vision for cycling?

They’re putting pedestrian crossing lights on signalised crossroads and replacing some footway paving with fancy stone. That will be the junction between Ordnance Hill and Acacia Road, two unclassified residential streets, both paralleled on each side by major through roads, but which have somehow become so busy with motorists cutting through that they need signals to manage the traffic and help people cross.

But it’s definitely a cycling scheme Westminster are spending the cycling money on, because alongside the expensive traffic signals and fancy stone paving, they’re going to paint advanced stop lines for cyclists.

Needless to say from schemes like these, Quietway 3 is going to be crap. Quietway 3 is not going to do the slightest to transform these streets into somewhere that, to quote the objectives of the scheme, people who are less confident in traffic will want to cycle. That these streets need signals and advanced stop lines to manage the traffic is shouting that they are a failure even before the letter ‘Q’ has been painted all over them. They are not, and will not be, the “quiet roads” that the mayor claims.

But that’s not what’s infuriating. Westminster misappropriating cycling funds is what Westminster does. It’s barely worth a sigh of resignation. What’s infuriating is that their behaviour could be seen a mile off, but the mayor has chosen to ignore every warning.

Reinventing the wheel

The rhetoric behind the Quietways is that this is some kind of innovation the likes of which we’ve never seen before, a radical programme that will deliver the transformation needed to make the mayor’s vision for cycling a reality. We’re told to wait and see how well it works rather than make premature judgements on twitter.

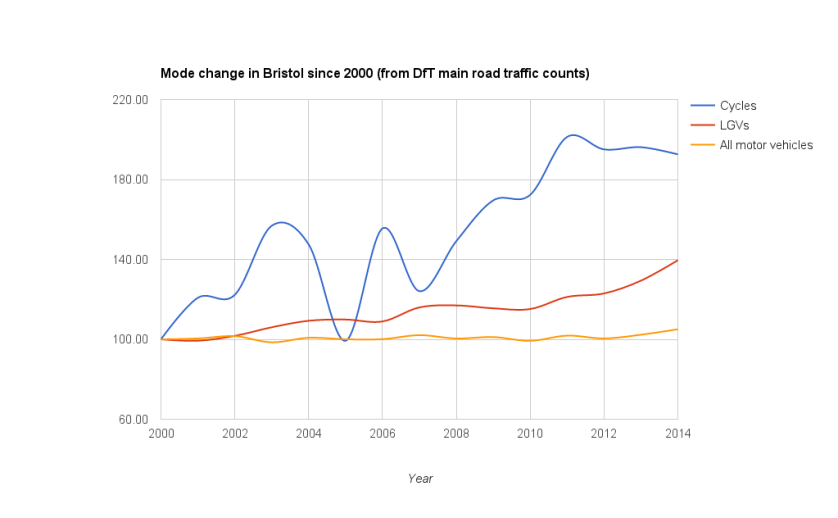

But we can see from Quietway 3 that there isn’t the slightest innovation between this and the the early 2000s London Cycling Network that failed before it — and which it largely follows. We know how well it will work because we have tried this countless times before. We know it doesn’t work, we know exactly why it doesn’t work, and we know what needs to be done differently to make it work.

The Quietways are failing for the same reason the London Cycling Network failed, and why the National Cycling Strategy before that failed, and why most of the Local Sustainable Transport Fund failed, and almost every one of the dozens of cycling policies since the 1970s that have proclaimed the same vision as this one have failed. They are being delivered piecemeal by nearly 3 dozen different local authorities and agencies few of which have the resources, expertise or adequate guidance to deliver it, few of which entirely share the mayor’s stated vision for them, and several of which are actively hostile to the objectives of the schemes they’ve been asked to deliver.

Boroughs and local authorities are well practised in redirecting ringfenced funds to their own priorities, as Paul M says of the LCN:

When we analysed how the City of London had spent its LCN grant money from TfL over the last few years, we found that typically the budget disappears down three roughly equal sized holes. One is the physical, tangible (for what it is worth) expenditure on paint and asphalt and — very occasionally –kerbstones. The second is spent on feasibility studies, impact assessments, traffic counts, yada yada yada, maybe even the occasional engineering design, carried out by consultants. The third, startlingly, is in effect a subsidy of the City’s own planing and highways departments’ salary bills.

This is the lesson that was learned from the 1996 National Cycling Strategy in an extensive report in 2005. It’s what led to the short-lived Cycling England, set up because the DfT discovered once again that trying to implement the National Cycling Strategy through grants to local authorities, who had their own agendas, didn’t work:

Weaknesses of the existing arrangements: Local authorities as delivery bodies

The first is how to work with local authorities, at present the main delivery agents, to deliver. Our main performance management system for local transport – the Local Transport Plan (LTP) system – identifies cycling as one of a large number of “products” that central government is purchasing from local government in return for the capital investment. But, in practice, our work with local authorities reveals that cycling, in most cases, is a significantly lower priority for transport investment than other outcomes, such as better public transport or small-scale highway improvements. Despite the transformation in the availability of local transport capital since 1997 and the increased investment in cycling under the LTP regime, levels of expenditure on cycling still lag well below those in successful cycling cities outside the UK. Central government cannot insist that local authorities adopt a particular cycling programme, nor would it want to, given that the direction of local government policy is to increase the autonomy of local government; however it can influence authorities through the LTP process.This suggests that, if cycling is genuinely a national priority, more diverse delivery mechanisms need to be introduced, to complement and increase the impact of what local authorities are doing.

Cycling England was created to stop our wasting money on an inefficient and ineffective way of delivering cycling projects through grants to local authorities. (It was abolished to save money, by, er, going back to that inefficient and ineffective system.)

None of this is news. We know very well what doesn’t work in delivering mass cycling, and the mayor has been warned again and again. But Sadiq Khan seems thoroughly determined to learn this lesson the hard way.

*This section has actually been a TfL scheme, so one department of TfL is happy to rip another just as much as the boroughs are.